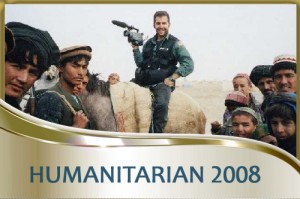

Beyond The Call

A rousing documentary that leaves the viewer breathless in anticipation of the next scene, Beyond The Call could be categorized as an action adventure feature. Except that it’s real life. Following several seemingly ordinary men as they bounce from one impoverished war-torn country to another (bringing food and medical supplies that they’ve purchased themselves to surprised victims), Beyond The Call has a clear message: doing for others incapable of doing for themselves is highly rewarding. Why else would anyone risk his life to help a stranger?

In between traveling to four continents in three months, filmmaker Adrian Belic took time to answer the following questions about his stirring film.

Q: How did you discover the interesting humanitarians that are the “stars” of your documentary?

€‹A: I met one of the stars, Ed Artis, at a screening of my previous film Genghis Blues at the Santa Barbara International Film Festival. He came up to my brother and me (we made Genghis Blues together) after the screening and Q & A. The short answer is, he told me a story I did not believe about the humanitarian work he and his friends do in war zones around the world. I was very intrigued and a few months later, after sitting down in an interview scheduled for two hours that went six hours, I knew there was something there. Then, I went with them on a trip and knew that it would be my next film.

Q: How long did it take you to complete this project?

A: I met Ed Artis in 1999 and began filming in 2000. We finished it at the end of 2005 and had the world premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York in May 2006. And now, I’ve been on the road with the film across the U.S. and around the world for more then a year.

Q: Do you know how the men acquire and manage the monetary donations?

A: The Knightsbridge guys have a non-profit 501(c)3 organization with a separate bank account.

Q: Have they experienced flak from any government agency about their unauthorized missions?

A: They’re small enough to fly under most governmental radar. I also think that most bureaucrats in most governments, if they check their humanity and common-sense, will realize that the Knightsbridge guys are really doing a lot of good and will get out of their way.

Q: The scene in the Karen refugee camp is so poignant. How did those men lose their limbs?

A: How do most people think the amazing Karen refugee soccer players lost their legs? Landmines. And the United States readers of your article should know that the United States is one of literally a handful of nations in the world that will not sign the landmine ban that has been signed by nearly every country in the world.

Q: How did you handle being around so much suffering while making this film?

A: I make films so that I can live life to the fullest and, one cannot do that with one’s humanity and emotions in check. There were a number of times where I would be quietly crying behind the camera as I filmed what I was witnessing. On numerous other occasions, I would sling my camera over my shoulder and help with whatever was happening that needed my help. In my films, I try not to just tell the audience what is happening or even show them that. Instead, I try to make them feel what I did and what those who I was with felt. It was very difficult coming back to the States between the filming and hearing that the United States should bomb places in the world back to the Stone Age and, that if everybody there were killed it would not be a loss. I cannot describe how infuriating it was to me that people in my country could be so ignorant and inhuman. I then began feeling sad for the majority of Americans who felt like that. As you see in the film, I was with people who were as in imminent danger from bombs, bullets and landmines as they were from hunger, disease or the bitter cold. Yet, they had the dignity to offer me their last cup of tea or piece of bread, and to welcome me and the Knightsbridge guys and say thank you for coming to help–with no desire to change their religion, mess with their politics or make a buck off of them. If one has the high honor to experience such human dignity and kindness, it will change one’s life. I wish for more people in the U.S., those that don’t seem to care if our government kills hundreds of innocent helpless people, to be fortunate enough to experience a gift like that.

Q: What were some of your scariest moments traveling in those foreign and sometimes hostile environments? Did you ever wonder if you’d get out of a situation alive?

Q: What were some of your scariest moments traveling in those foreign and sometimes hostile environments? Did you ever wonder if you’d get out of a situation alive?

A: There were the times while traveling through Afghanistan by car and being stopped by bandits at illegal road blocks with machine guns pointed at us and screaming at us in languages we did not understand. There were the government officials in faraway lands that threatened us with imprisonment with little chance of appeal. There were the single lane mountain roads with thousand-foot drops to one side and a landmine field to the other side with a bus heading straight for our car. And then, there was the time in October 2001 that we had to get out of Afghanistan and back into Tajikistan hidden in a 20-foot container. I thought of the things we were told when we were little kids and went off wandering in the wilderness: “Remember to tell your parents or the authorities where you are going”; and, I realized that no one know where I was. The 20-foot container was probably the scariest.

Q: One of the characters, Ed Artis, has a heart attack in the film. How is his health now?

A: Ed has had six heart attacks since the first one in the film, but he keeps on doing what he does best–helping those in great need.

Q: What are some of your past projects?

A: My brother, Roko, and I made the documentary feature Genghis Blues. It was our first film after graduating from college. We were very fortunate to win the Sundance Audience Award and were honored with an Academy Award nomination.

Q: What are you working on next?

A: I have a number of projects in the works in Cuba, Venezuela, Laos, Burma (Myanmar), and Indonesia.